- Public Policy

- Leadership

- Funding

- News & Events

- About the Center

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

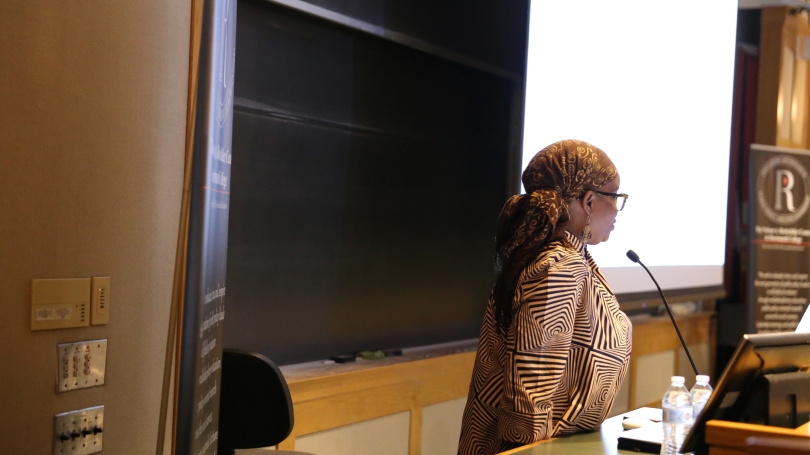

On Tuesday, October 8, 2019, community organizer, educator, and prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba spoke in Filene Auditorium. Her talk, “Free Them All: Defending the Lives of Criminalized Survivors of Violence,” emphasized what she considers the tragic flaws in the United States criminal justice system by highlighting how its laws and legal systems structurally disadvantage some groups based on gender and race.

Kaba grew up in New York City in the 1970s and 80s in what she called a “political family.” Her father was active in anticolonialism in Guinea and “was always talking about politics in some sort of way.” While still in high school, she began working in anti-police brutality work, and in college became active in the anti-apartheid movement at McGill University. “I’ve been working on the issues that I’ve cared about since I was a teenager to this day,” she said.

Rather than focusing on broad negative trends in the criminal justice system, Kaba opted to drive home her point by focusing on the story of how the criminal justice system impacted one girl, Bresha Meadows.

Meadows is a survivor of domestic violence. During her childhood, “Bresha, her siblings, and her mother were all abused by her father,” Kaba explained. At no point did the authorities step in to alleviate this violence, even though the abuse was common knowledge to Meadows’s neighbors, teachers, and counselors at school. This lack of intervention led to further abuse, and at the age of fourteen, Meadows was charged with the aggravated murder of her father after defending herself from one of his attacks. Rather than helping Meadows, Kaba said, our criminal justice system allowed her abuse to continue and tried to put her behind bars once she was forced to defend herself.

This led Meadows to join the “84 percent of girls in juvenile detention who have experienced violence prior to incarceration.” Her struggle, Kaba argued, is emblematic of a criminal justice system that preys on the most vulnerable people in society, particularly young women of color. “We don’t talk enough about black girls,” Kaba emphasized.

Recognizing that the criminal justice system was silencing Meadows rather than helping her, Kaba organized a “people’s defense” to help her through the #FreeBresha campaign. “We refused to accept that by defending her life she should be criminalized,” Kaba said forcefully. The campaign fought to have all charges against Meadows dropped, employing petitions, protests, mass letter-writing, and the creation of artwork meant to illustrate Meadows’s humanity. They were only partly successful, and Meadows accepted a plea deal that kept her in juvenile detention for a year and mandated that she spend an additional six months in a mental health treatment facility.

Kaba, clearly upset over the injustices to which she had borne witness, offered her insights from the experience. The attempts by the criminal justice system to make Meadows “disappear” were not an aberration, but rather the system “working exactly as intended,” Kaba said. It was a manifestation of a “white supremacist society” that views agency on the part of people of color, especially women, as aberrant. According to Kaba, Meadows’s act of self-defense mandated prosecution by the criminal justice system because “sanity is defined through the lens of whiteness and domination.”

When asked about the changes she would like to see to the criminal justice system adopt to help address these types of abuses, she drew a distinction between “reformist reforms” and “non-reformist reforms.” What she aims to do through non-reformist reforms is to decrease the power of the “prison-industrial complex” through decarceration and decriminalization — shrinking the number of crimes, police officers, prisoners, and prisons.

Reformist reforms, such as adding body cameras to police officers, “legitimize the system” and “put obstacles in the way” of achieving a more just society, according to Kaba. “The camera is pointed at you,” she noted. “You don’t want to give a system you’re trying to take power away from more power.” She instead seeks a “transformation of everything” — not just in the criminal justice system, but in wider society.

Kaba left the crowd with a powerful glimpse into the structural problems inside the U.S. criminal justice system, as well as a call to action to prevent such injustices in the future.

Kaba’s visit to Dartmouth was co-sponsored by the Ethics Institute and the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program, and included class visits to four sections of the Sex, Gender, and Society course and a lunch workshop for the Dartmouth community on transformative justice. Her public event was the Roger S. Arron ’64 Lecture, supported by the Dartmouth Lawyers Association and the Dartmouth Legal Studies Faculty Group.

Written by Ben Vagle ’22 and Kyle Mullins ’22, Rockefeller Center Student Program Assistants for Public Programs