- Public Policy

- Leadership

- Funding

- News & Events

- About the Center

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

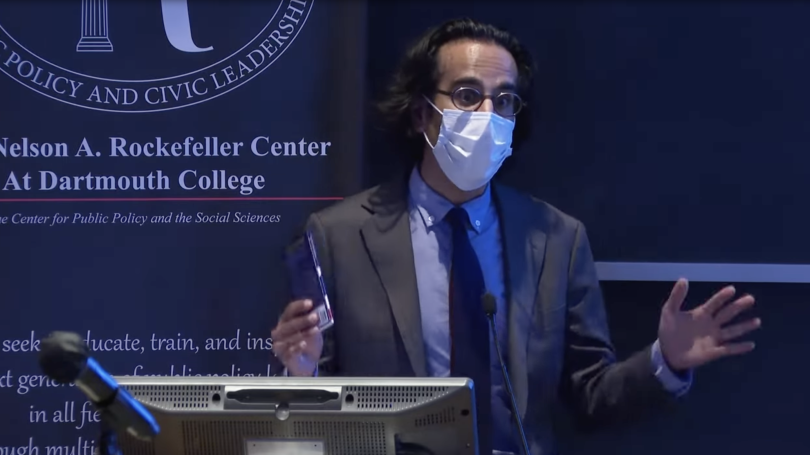

On September 20, 2021, the Rockefeller Center hosted its first in-person event in eighteen months when Professor Sonu Bedi, the Joel Park 1811 Professor in Law and Political Science at Dartmouth College delivered the annual Constitution Day Lecture. Introduced by Associate Professor of Government Julie Rose, Bedi implored his audience to explore the Constitution in a different way: not as a Democrat or Republican, or as an advocate or critic of the Supreme Court, but as a Constitutional scientist embracing the disagreement fueled by competing legal philosophies within the text itself.

To begin, Bedi introduced the work of Frederick Douglass, an African-American abolitionist, orator, and newspaper publisher who argued that the U.S. Constitution is an anti-slavery document. In his writings, Douglass made a clear distinction between the "American Constitution" and the "American government," which he argued are "distinct in character as is a ship and a compass." "The Constitution may be right, the government is wrong… if the government has been governed by mean, sorted, and wicked passions, it does not follow that the Constitution is mean, sorted, and wicked," Douglass wrote. Douglass's clear distinction between the Constitution as an actual document and the government, which uses the Constitution as a guide, Bedi explained, is critical to understanding the true implications and meanings of such an important founding document. By examining the document itself rather than the government, which has taken it upon itself to interpret the document in a specific way, Bedi emphasized, "this is how we begin as scientists of the Constitution."

As scientists, Bedi argued, there are three fundamental functions of the Constitution that are critical to examine. The first is that the document arranges and limits public power. The second is that the Supreme Court has the power to say and justify what those arrangements and limits are. Most importantly, as Supreme Court opinions are also "part of the science" of the Constitution, "there is a practice of disagreement on the Court in exercising that [public] power." This practice of disagreement is not only the foundational point of Bedi's talk, but it lays the groundwork for many of the debates around the writings of the Constitution and their interpretations as local and federal laws that we see today.

Well, where does this "disagreement" emerge from? To answer, Bedi outlined two important models of a republic outlined in the Constitution: a traditional republic and a modern republic. While the traditional or anti-federalist republic advances a state-centered arrangement of power under which the limits on powers are treated as rules, a modern (federalist) republic runs under a nation-centered arrangement of power where standards (which "invite a kind of flexibility") limit power. However, even in the case of the modern republic, states continue to play an important role: "states are how we Americans interact with the Constitution." Despite these differences, Bedi argued, "the Constitution affirms both a traditional republic and a modern republic," creating the importance "practice of disagreement" we see today.

However, just because the Supreme Court and the Constitution entertain a practice of disagreement does not mean that agreement among Supreme Court Justices is out of the question. According to ABC News, Bedi noted, 67% of opinions in the Supreme Court's past term have either been unanimous or nearly unanimous (with only one justice dissenting), noting that a traditional and modern republic can at times, "reach the same outcome."

Finally, Bedi emphasized the distinction between political philosophy, and politics, one that is often significantly blurred under the lens of the press and current-day politics. As an example, he explained, two competing policy ideas—such as spending on the national military and spending on national social programs—may be favored by different political parties but can both fall under the purview of a single legal philosophy: a modern republic. "Politics is one thing… we can disagree about politics… but both political philosophies are appealed to on either side," Bedi argued, suggesting that this disagreement "is not a bug, but rather a feature" of the Constitution that should be embraced.

And it is this very disagreement, Bedi said, that remains the key to what the very Founders of the intended from the start: a more perfect Union.

-- Written by Shawdi Mehrvarzan'22, Rockefeller Center Student Assistant for Public Programs