- Public Policy

- Leadership

- Funding

- News & Events

- About the Center

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

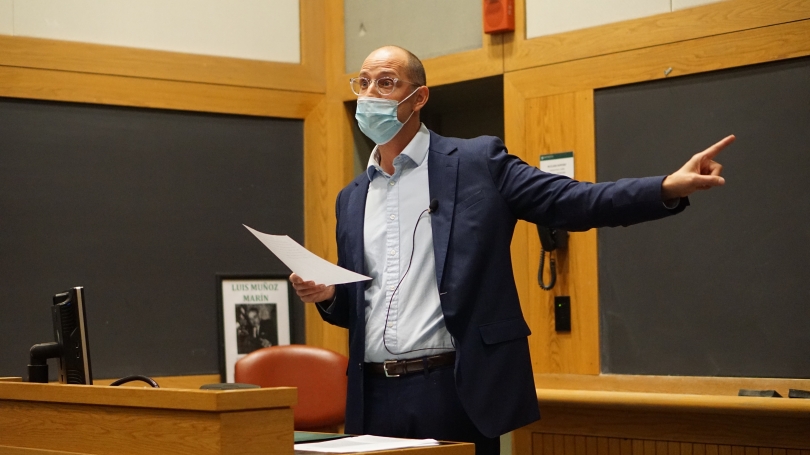

On Wednesday, October 27th, 2021, Noah Phillips '00, a commissioner on the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and former Chief Counsel to U.S. Senator John Cornyn, of Texas, met with Dartmouth students and community members to deliver the Thurlow M. Gordon 1906 Lecture at the Rockefeller Center.

The FTC is a government agency that "protects consumers and competition by preventing anticompetitive, deceptive, and unfair business practices through law enforcement, advocacy, and education, without unduly burdening legitimate business activity." The Commission is led by five commissioners, three of whom are Democrats and two of whom—including Commissioner Phillips—are Republicans.

Commissioner Phillips used the occasion to offer his thoughts on the state of the FTC and of antitrust policy in the United States more generally. Before beginning, he emphasized that "what I'm going to say tonight is not the view of the Federal Trade Commission and is not the view of my fellow commissioners. It's really not the view of my fellow commissioners."

To start, Phillips recalled attending another Thurlow M. Gordon Lecture. This one, however, occurred in 1998 and was delivered by Joel Klein—who at the time was the Department of Justice's Assistant Attorney General in its antitrust division. Klein spoke about the DOJ case from that year against Microsoft. Though more than 20 years ago, "that case continues to loom large. The popular attention that it received, the decisions rendered… and of course that the target was a large tech corporation," all recall antitrust actions today.

Further, Phillips acknowledged the life of Thurlow Gordon, recalling that he lived through two important periods of antitrust reform. "My goal tonight," Phillips said, "is to lay out a little bit of that history and demonstrate why some of the calls for reform today [are] inconsistent with that history. Antitrust law was then, is now, and should remain about one thing: competition."

To do this, Phillips outlined three periods of antitrust history. The first came at the end of the 19th century, when the U.S. passed the Sherman Act to begin breaking up large trusts—such as Standard Oil—which had developed during America's rapid industrialization. In 1914, President Wilson further reformed U.S. antitrust practices by calling for legislation to bring greater clarity to the enterprise, resulting in the passage of the FTC and Clayton Acts. Notably, all these laws "by their explicit terms… focused on competition."

However, "much of the debate about antitrust today… is about antipathy toward big corporations, it's about the unsettling nature of new technologies, it's about political power, it's about who should run American companies," Phillips emphasized. "Much of this debate, too much in my mind, is not about competition."

Building on this point, Phillips argued that the Biden Administration has been "repurposing antitrust away from competition," highlighting some areas in which this appears to be the case. For instance, Phillips noted that recent Biden Administration executive orders have imposed a glut of regulations. "While regulation can encourage competition, often it can have the opposite effect," Phillips said, noting that many antitrust regulations being passed today have an overtly anticompetitive bent, for example, barring large firms from entering new markets.

Further, Phillips advanced an argument about the role of the FTC itself. "My view of my job is not to be responsive to an urge that Congress has," rather, Congress should "express [its] view through legislation… and my job is to enforce those laws." In other words, Phillips believes the FTC should avoid regulation via executive fiat and clearly adhere to legal precedent.

Finally, Phillips views some concerns that are being treated as antitrust issues, such as the influence of technology companies, as potentially having little to do with competition; it isn't clear, for example, that breaking up big technology companies will enhance user privacy. This is because, Phillips says, private firms are driven by profit, and technology firms often generate income by mining user data. In other words, smaller, privately owned technology companies may have equal incentive to compromise user privacy for profit.

Clearly, Phillips said, compromised privacy and many other social ills are problems that require action. However, "antitrust is not, and has never been, a general warrant to punish companies that some, or even many, don't like. Antitrust is about competition, and it should stay that way."

Written by Ben Vagle '22, Rockefeller Center Student Assistant for Public Programs