- Public Policy

- Leadership

- Funding

- News & Events

- About the Center

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

This article is part of a series of articles honoring Dartmouth Alumni who have served in public office and demonstrated their commitment to the ideals of public service, leadership, and civic engagement.

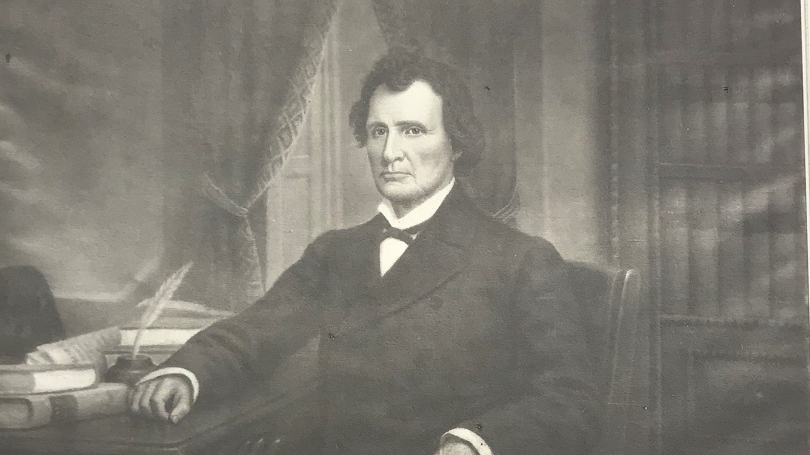

A man of single-minded purpose, Thaddeus Stevens, Dartmouth class of 1814, spent his life vehemently fighting for racial and social equality in America. Historian Hans Trefousse noted in a biography on Stevens that he "was one of the most influential representatives ever to serve in Congress.” According to Trefousse, Stevens “dominated the House with his wit, knowledge of parliamentary law, and sheer willpower….” However, Trefousse also concludes that Stevens’ influence was often limited by his extremism.

Stevens sense of idealistic democracy and his unwillingness to compromise his beliefs even impacted his undergraduate experience. During his college years, he transferred to Burlington College (later known as the University of Vermont) for three months just so he could perform an original play that he had written about Switzerland’s struggle for democracy and freedom. Ironically, he did so in protest to a Dartmouth policy that no oration could be “exhibited” within four miles of Hanover until it had been “revised and approved” by someone in authority. A policy which Stevens found unacceptable. As a result, Stevens attended UVM from May to July of 1813, just long enough to present his play The Fall of Helvetic Liberty, returning to Dartmouth in the fall. This was not the first time Stevens pushed the boundaries for his beliefs, nor would it be the last.

Stevens did not set out to be a career politician, but he did view politics as an effective means to creating change on matters that he believed in passionately. Stevens served four non-consecutive terms between 1833 and 1841 in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. During those years, most of his time was spent focusing on public education. He credited education as his own means for escaping poverty and felt every child deserved a similar chance. Stevens saw education as the greatest path to equality and without it, he believed the country would remain divided along racial and socioeconomic lines. He helped pass the first law in Pennsylvania to fund public education and was later recorded as saying he considered passage of that law his greatest triumph in his political career.

Although Stevens valued his work in public education above all else, today he is largely remembered for his abolitionist convictions. That reputation began in 1836, when Pennsylvania delegates attempted to revise the state constitution by adding the word “white” and effectively denying blacks the right to vote. Stevens refused to sign it. This act was just the beginning of his involvement in the abolitionist movement. Stevens entered Congress in 1849 and served as a Representative for the Whig party in the United States House from 1849-1853, where he argued strongly against the Compromise of 1850. He argued that the Compromise was also a compromise on human and constitutional rights, because it allowed for new territories to become slave states. He ultimately left the Whig caucus in 1851, because they did not support his attempts to repeal it.

Stevens was reelected to the House under the Republican Party in 1859 and supported the Lincoln administration throughout the Civil War years. When President Lincoln was assassinated just six days after the war ended, Stevens rightly feared that all the Republicans efforts during the Civil War would be immediately reversed by Johnson. He acted quickly by introducing and pushing through Congress a resolution to create a joint committee on reconstruction on which he served. The following year, Stevens was instrumental in passing Civil Rights Act of 1866 and in the creation of the Fourteenth Amendment. He also served as one of the seven prosecutors during the Johnson impeachment trial.

Stevens was spared from seeing President Johnson’s reversal of many of the reconstruction policies that he worked so hard to secure, as he passed away August 11, 1868. So beloved by his constituents, in the primaries held to fill the vacancy left by his death, the Republican electors of Lancaster County unanimously voted, Thaddeus Stevens.

Written by Allison Tong ’20, Student Researcher for the Dartmouth College Public Service Legacy Project.

Dartmouth’s Rauner Special Collections Library has some of Stevens’ papers in its collection. Among those in Dartmouth’s collections are notes for a speech he delivered in 1866 on voting rights, a personal letter of recommendation written on Ways and Means Committee stationery, and the speech Stevens delivered at his 1814 Dartmouth commencement. See slideshow on Dartmouth’s flickr site.