- Public Policy

- Leadership

- Funding

- News & Events

- About the Center

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

This article is part of a series recognizing Dartmouth Alumni who have served in public office and demonstrated their commitment to the ideals of public service, leadership, and civic engagement.

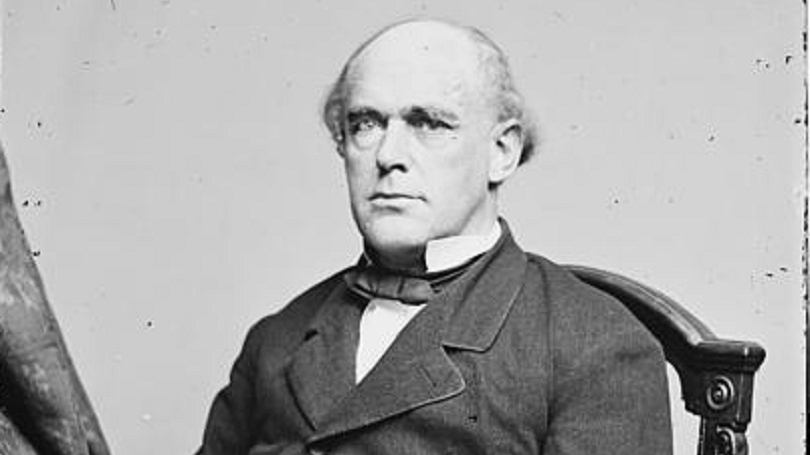

A graduate of the Class of 1826, Salmon P. Chase is one of just three people to have served as a state governor and in all three branches of the United States government. After practicing law in Cincinnati, Chase entered public service: he served as U.S. Senator from Ohio, Governor of Ohio, U.S. Secretary of Treasury, and Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Chase is perhaps best remembered for his contributions to the Union during the Civil War, during which he served as U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. His efforts in this office are remembered to this day: Chase Bank, founded in 1877 and still in operation today, was named in honor of Chase and his help in financing the Union.

Chase’s economic contributions often overshadow his contributions in another area. As a young lawyer within the anti-slavery movement, he was one of the country’s most distinguished “constitutional abolitionists.” Known to rarely refuse a case of this sort, Chase was nicknamed “Attorney General for Fugitive Slaves.”

In 1837, at twenty-nine years of age, Chase brought to his local judge a writ of habeas corpus for the freedom of a runaway slave named Matilda. Despite her protected status in free territory, Matilda was captured under the Fugitive Slave Act, a law that authorized slave owners to seize and detain runaway slaves. Defending Matilda, Chase challenged the constitutionality of fugitive slave laws. Despite Chase’s defense, Matilda ultimately lost the case: the judge ruled that she be returned to the slave catchers who auctioned her off in New Orleans.

Years later, Chase presented before the United States Supreme Court a more developed argument against the Fugitive Slave Act. Chase argued in Jones v. Van Zant that fugitive slave laws go above and beyond Congress’s power of ratification, and that no section of the Constitution empowered Congress to create or enforce conditions of slavery, which included the enforcement of slavery upon individuals in free territory. Additionally, Chase argued that the act violated the Due Process Clause by authorizing the seizure of fugitive persons without fair process.

Chase was denied oral argument before the Court because a previous ruling, Priggy V. Pennsylvania, rejected comparable arguments. Despite his defeat, Chase’s argument was published and circulated widely across the country and served as a foundation for future challenges to the Fugitive Slave Act.

Through his legal practice, Chase's reputation as a constitutional abolitionist had significant influence on his political career. In 1848, Chase helped to develop the Free Soil party and was elected in 1849 to the U.S. Senate on the Free Soil platform. Throughout his career in the Senate, and as the Governor of Ohio, Chase rejected the extension of slavery and championed against the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Due to his commitment to anti-slavery efforts, coupled with his efforts to secure voting rights for black citizens, Chase was prevented from ever securing a bid for presidency.

Submitted by Makena Kauhane '19, Student Researcher for the Dartmouth College Public Service Legacy Project.