- Public Policy

- Leadership

- Funding

- News & Events

- About the Center

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

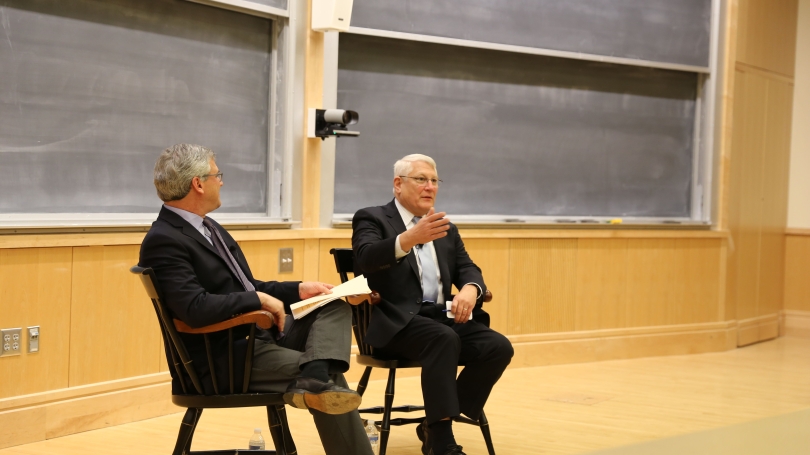

On Tuesday, November 12th, 2019, General Carter Ham came to Dartmouth for an event co-sponsored by the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center and the John Sloan Dickey Center titled “War, Peace and Remembrance.” During the event, Ham and Daniel Benjamin, the director of the Dickey Center, reflected on the meaning of Veterans Day and contemporary issues facing the U.S.military.

General Ham, a United States Army Commander who served as the second Commander of the United States Africa Command, described himself as having grown up in an upper-middle class family with the expectation of going to college; however, he describes his time at university as “just not feeling right,” and one day choosing to enlist in the army instead. For Ham, this ignited a career that made him one of the few US army members to rise from the rank of private to general in the US army.

General Ham’s began with an acknowledgement of the sacrifices made by the millions of Americans who have served in the military. Pointing to the 101st anniversary of the end of World War I, which happened on November 11th, he discussed the dilemmas WW1 commanders faced on Armistice Day in choosing whether or not to risk sending their troops against enemy lines when peace was imminent. For Ham, this was a poignant way to reflect on “the challenges and dilemmas we put soldiers in” over Veterans Day.

Discussing Veterans Day itself, Ham bluntly stated that he wished “we didn’t have Veterans Day,” because the sacrifices made by the US military should be something of which all Americans are fully aware. But Ham observed that “fewer and fewer of us have a direct connection with the U.S. Military,” increasing the distance between the public and military and making reminders of military service, like Veterans Day, necessary. Ham commented that while relationships between civilians and the military remained strong in areas like Arlington that host a direct military presence, the relationship between civil society and the military “starts to break down a little bit when you go below the national level.” Ham said “I worry a bit about that,” reminding the audience that “this is your army.”

The conversation then pivoted to the treatment of veterans. Ham, who now directs the Association of the United States Army, a private advocacy notes with pride that his organization “has been aggressively implementing veteran programs.”; however, there are issues among the veterans community that deeply disturb him, like “veteran homelessness and suicide.” To Ham, a homeless veteran “does not comport with… fairness.” Ham made clear that more action to support the veterans community is needed, saying “we’ve got to come to grips with how to meet our obligations to the veteran community.”

Benjamin then pressed Ham on his views about the protracted wars that our military has been engaged in. Ham replied that “ending forever wars is not a strategy, it’s a nice bumper sticker” but conceded that there has been “an overreliance on the military instrument” in U.S.foreign policy. He described the military as not being equipped to conduct U.S. foreign policy unilaterally and advocated for “greater levels of resourcing” on the “diplomatic front.”

General Ham also expressed deep concern about the recent forays of retired military officials like Michael Flynn into politics. This is because he thinks a more political military could undermine communication between military officials and public officials by leading these groups to regard one another as potential political rivals instead of coworkers. “It is not appropriate for former senior military officials to opine on political matters,” Ham said firmly.

Finally, an audience member asked Ham to detail his struggles with mental health while in the service, and more generally to discuss the problem of PTSD in the military. Ham described his own struggles adjusting to returning home from duty, feeling detached from his family and overly absorbed in his duties. For Ham, it was when he reunited with his dog and burst into tears that “it became evident to me that I needed help,” which he received from an Army chaplain. Discussing post-traumatic stress more generally, Ham commented that it “remained very underappreciated and very underdiagnosed,” but he made clear that “if it was ok for a general [like Ham] to say publicly I needed a little bit of help coming back from a combat zone, then maybe that’d help somebody else.”

-Written by Ben Vagle ’22, Rockefeller Center Student Program Assistant for Public Programs