- Public Policy

- Leadership

- Funding

- News & Events

- About the Center

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

This article is part of a series recognizing Dartmouth Alumni who have served in public office and demonstrated their commitment to the ideals of public service, leadership, and civic engagement.

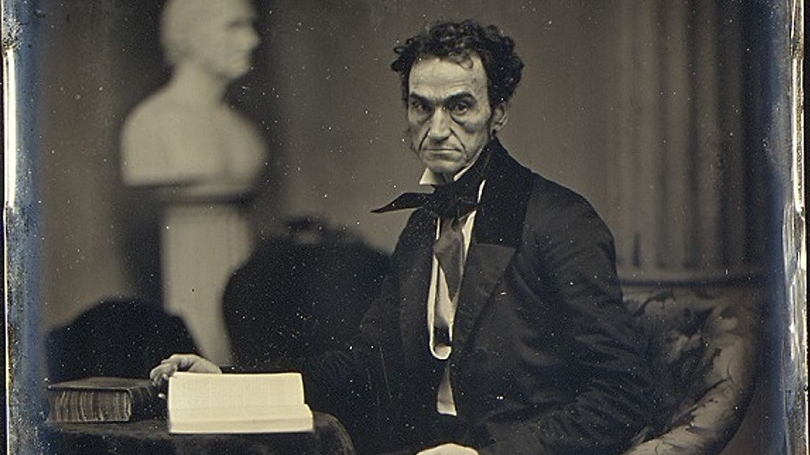

Rufus Choate, Dartmouth Class of 1819, was a lawyer, orator, and politician who devoted himself to whatever task was before him. Best known for his career as a lawyer, he is said to have never lost a case, always performing the most eloquent speeches in defense of his clients. As a politician, his career was marked by the multitude of passionate speeches he gave, his dedication to his constituents, and the morals he stood for. He also lived his life as a continual scholar, never abandoning the learning that marked his time at Dartmouth. One of his biographers, Reverend Adams, noted that he was defined by “one of his prominent characteristics, the seizing upon every means to fit himself for every task with which he consented to grapple. It was in the genius, the nature of the man, to master every subject appertaining to his calling.”

Born in 1799 in a farming community in Massachusetts, he showed a very early propensity for reading, and entered Dartmouth in 1815 at the age of 16 as one of the youngest members of his class. At Dartmouth, he was known as a diligent and faithful student with extraordinary progress in mental discipline and study. Fellow students testified to “the supremacy which he held here, in the unanimous judgment of fellow students.” His time at the college coincided with the “Dartmouth College Case,” in which the state of New Hampshire, supported by some of the trustees of the college, tried to annul Dartmouth’s charter and make it a public university. In 1817, Choate, who was a member of the Social Friends, moved the society's library of 2000 books from state-controlled buildings into his own room, leading to his arrest and further animosity between the two sides of the controversy. The dispute with the state of New Hampshire ended in 1819 with the Supreme Court decision to uphold Dartmouth’s charter, in a case successfully argued by Daniel Webster, Dartmouth Class of 1801. It was this defense of his school by Webster that drove Choate to become a lawyer and pursue a similar career in oratory and argument.

He graduated Dartmouth as valedictorian with the highest honors and spoke at graduation. His legacy survives at Dartmouth in the naming of Choate Road, the Choate dormitories, and the designation of a “Rufus Choate scholar,” which is given to the top five percent of every graduating class.

After attending Harvard Law School for one year and spending some time in Washington, Choate earned admission to the bar in 1823 in Massachusetts and began practicing. His first few years were especially trying, causing him to question his chosen profession. Speaking about his chosen profession, Choate said: “[it] seemed to possess a two-fold nature: it has resisted despotism and yet taught obedience. It has recognized the rights of men and yet has reckoned it always among the the most sacred of those rights to be shielded and led by the divine nature and immortal reason of law.” He eventually established a practice in Massachusetts and soon became well-known as a lawyer throughout New England.

Alongside his law practice, Choate served in government, first in state legislature (1825-1829), then as a representative for Massachusetts in the House of Representatives (1831-1835), and finally as a senator for Massachusetts (1841-1845). In government and in law he was always tied to his mentor, Daniel Webster, who was said to be his only equal, and with whom he founded the Whig party in Massachusetts. Choate’s legacy exists in the form of the speeches he gave while in office, which marked him as eloquent and persuasive. While he was a senator, he delivered numerous speeches on topics ranging from the tariff to funding the Smithsonian Institute, but all centering on his individual perception of American nationality, particularly that patriotism was the result of effort and will, not a spontaneous inherited sentiment. His career in government and his work as a lawyer came together to make him an advocate—for his clients and for his constituents.

One of his biographers, Albert Stickney, explained: “With every talent that could make a man a great advocate—with a marvelous memory, a keen logical intellect, a sound intellectual judgment—he had now acquired a large professional experience and a very complete professional training.” Choate practiced law until his death, continually pursuing new intellectual and professional endeavors.

Submitted by Bella Horton '20, Student Researcher for the Dartmouth College Public Service Legacy Project.